Since the earliest days of aviation, we have got used to aircraft looking largely alike. A lot has changed in aircraft technology, but the basic fixed-wing design remains the same. A blended wing concept has been experimented with for decades, with limited success in the commercial sphere. But as manufacturers and airlines focus ever more on efficiency improvements, could we see a new shape of plane in the future?

The fixed-wing aircraft

The purpose of the aircraft wing is to produce lift whilst moving through the air. The idea of using a wing structure for flight was incorporated into the earliest concepts of gliders and flying machines. For example, Leonarda da Vinci’s designs in the 16th Century were based on mechanical reproduction of extended bird wings.

The first powered aircraft to fly – with the Wright Brothers in 1903 – was based on a double fixed-wing design. This evolved through several further concepts. Other significant advances included introducing stick controls for roll and pitch with the Bleriot VII and metal airframes during World War I (the German Junkers J1 was the first to feature this).

These early aircraft have set the standard for much that has followed. Naturally, a great deal has changed in designs over the years, with aircraft becoming larger, using lighter and composite materials, and employing significant aerodynamic improvements. But the basic appearance and operation of the fixed-wing are the same.

Of course, most aircraft have long moved to a single wing design. Still, the position of below, above, or in the middle of the fuselage varies based on aircraft design and purpose.

Moving to a blended wing design

There are a variety of fixed-wing designs in use. Some of the smaller aircraft use a simple rectangular fixed-wing (such as the Piper PA 38). Most larger jets used swept-back wings. A few military aircraft have used swept-forward wings. And a delta wing is commonly used for high-speed military jets, with more efficient supersonic performance. Concorde, of course, also used a form of the delta wing.

The blended wing, though, is different from any of these fixed-wing designs. A blended wing aircraft has no definite fuselage and instead ‘blends’ the wing and fuselage into a single construction. The entire aircraft then provides the lift required for flight. This explains its other name of a ‘flying wing.’ The increased fuselage space can then be used for carrying payload – that could include fuel, avionics, cargo, or passengers.

Early blended wing plans

The blended wing is not an entirely new concept. There was experimentation with it from Germany, USSR, Britain, and the US since before the Second World War. In military use, the blended wing brought advantage in efficiency as well as radar detection.

There was interest too in developing it for passenger use. British manufacturer Armstrong Whitworth developed the AW 52, with two prototypes flying. But research failed to lead to any production aircraft.

US manufacturer Northrop Grumman was also interested. It developed the experimental YB-35 and YB-49 bomber aircraft. And in the 1950s, it released plans for a passenger flying wing aircraft but never proceeded with development.

Challenges with blended wing design

There were several difficulties that prevented blended wing aircraft from going further. A blended wing is often presented as the theoretically most efficient aircraft design, with reduced drag. It is also lighter than a traditional fixed-wing design, further improving efficiency.

But in reality, this is hard to achieve. The fuselage area needs to be deep enough to be useable, and this can increase drag. In addition, control and stability is a challenge to overcome.

There are also practical challenges that have affected commercial design. These included:

- Such an aircraft would have a large internal fuselage area, so would target the high-capacity aircraft market only. Would this be worth the high cost of development in an unproven area?

- There could be challenges operating at smaller airports (as we have seen with the A380 due to its wingspan).

- Placing engines within the airframe structure rather than external pods would lead to access, as well as potential safety issues.

- It would be subject to the same safety requirements for emergencies and evacuation. The Boeing 747 was originally proposed with a full-length upper deck, but this could not be made to work under evacuation limits. Would this be possible for such a wide internal cabin?

Current proposals for blended wings

As jet aircraft have developed since the 1950s, there has been little discussion of switching to a blended wing design. Efficiency improvements have focussed on upgrading engines, wing design, and lighter weight components.

The blended wing through remains a promising next step in efficient design – if anyone can make it work. In recent years, there has been some renewed interest. It is still, of course, very early stages, but model prototypes have now taken flight.

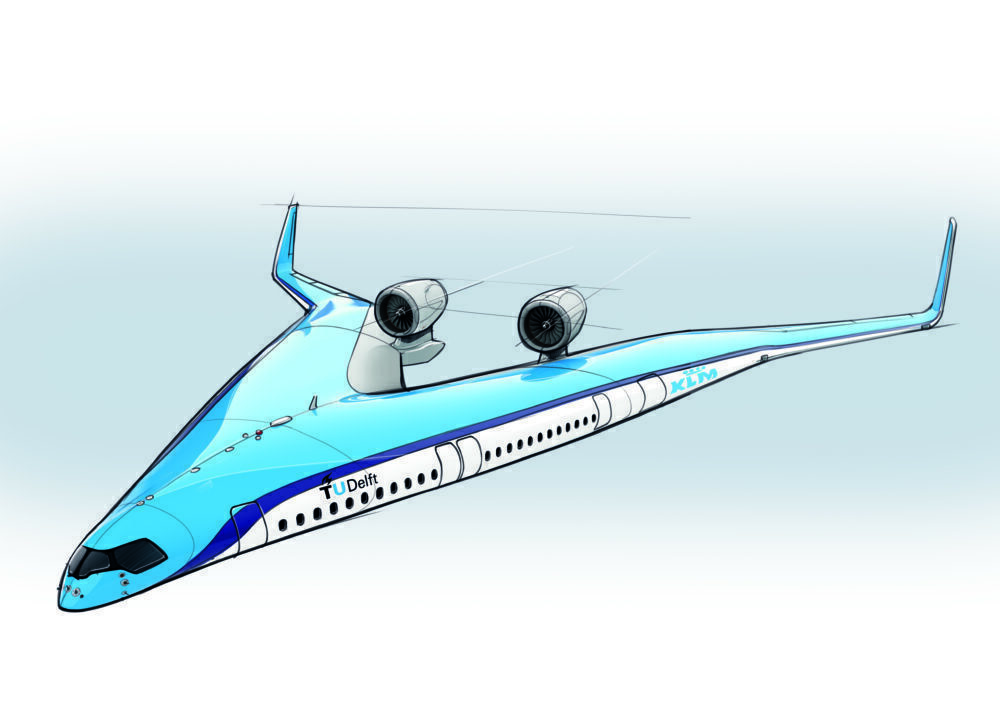

KLM’s Flying-V design

One such proposal is from KLM, working together with the Delft University of Technology on a ‘Flying V’ project. This is a delta-shaped aircraft with passenger cabins down each side. KLM claims that this could offer 20% more fuel efficiency than the A350.

The Flying-V would be a long-haul, high-capacity (around 314) aircraft. With its blended design, it would be shorter than the A350 but have a similar wingspan (important, of course, for airport operations).

KLM has been working with TU Delft since 2018 and remains committed. A first milestone was reached in September 2020 when the team flew a first model Flying-V. This was a 22.5kg model with a 3.06-meter wingspan.

This summer, a team of researchers, engineers and a drone pilot of @tudelft travelled to Germany for the first real world test flight. After a period of extensive testing in the wind tunnel and a series of ground tests, it was time to find out: can the Flying-V actually fly? pic.twitter.com/Lq4f12oX0l

— KLM (@KLM) September 1, 2020

KLM CEO Pieter Elbers explained at the time how the project fits with KLM’s vision for improved efficiency and sustainability. He said:

“We were very curious about the flight characteristics of the Flying-V. The design fits within our Fly Responsibly initiative, which stands for everything we are doing and will do to improve our sustainability. We want a sustainable future for aviation, and innovation is part of that. We are therefore very proud that we have been able to achieve this together in such a short period of time.”

Proposals from Airbus

Airbus is the first of the major manufacturers to reveal a future blended wing design. It revealed its design at the Singapore Airshow in February 2020, along with a three-meter wide prototype model that had already flown in 2019. The Airbus project is named ‘MAVERIC.’ This stands for Model Aircraft for Validation and Experimentation of Robust Innovative Controls.

Adrien Bérard, MAVERIC Project Co-Leader, explained Airbus’ commitment to the project:

“At Airbus, we understand society expects more from us in terms of improving the environmental performance of our aircraft. MAVERIC’s blended wing body configuration is a potential game-changer in this respect, and we’re keen to push the technology to the limit.”

A blended wing-aircraft also features in Airbus’ ZEROe range of hydrogen-powered aircraft. The first two aircraft are based on a regional turboprop and turbofan narrowbody concept, but with hydrogen as a fuel source. The third proposal is for a blended wing aircraft with a capacity of around 200. Airbus is targeting the first ZEROe aircraft in service by 2035 – but this will not be the blended wing design.

Works for hydrogen storage

One of the advantages of the blended wing design is the larger fuselage space. This has particular relevance these days as airlines and manufacturers are considering a potential future switch to hydrogen as a fuel source. One of the challenges of hydrogen fuel is the additional space needed to store fuel, especially for long-haul flights.

Airbus’ ZEROe proposals highlight this. Not only would the blended wing design be based on hydrogen as a fuel source, but the additional fuselage space could also be used to store hydrogen.

Inside a blended wing cabin

So, if a manufacturer can make it work, a blended wing aircraft could offer more efficient operation for airlines and easier transition to hydrogen fuel. But what would it be like for passengers?

The cabin would not necessarily be larger overall but would be a totally different shape to what we are used to now. This could, of course, mean wider seating (how does a four or five aisle 20-across cabin sound?) So far, though, we are seeing innovative new designs going along with the early technical proposals.

Under its MAVERIC project, Airbus proposes economy seating in traditional rows in the central area, with swiveling business class seats arranged around the outer part of the cabin.

KLM’s V-Flyer project has released some more innovative new concepts. This includes passenger bunk beds making use of the curved walls of the fuselage. It has also looked at staggered economy seating for more privacy and two-tier hanging seats.

There have been a few historic aircraft that have really changed aviation. Could the blended wing aircraft be the next? There are still many unknowns, both from the engineering and passenger use aspect. Feel free to discuss these and share your thoughts in the comments.

from Simple Flying https://ift.tt/3wms3gQ

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment